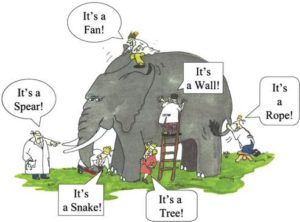

How do you know what you know about Islam? Do you “know” that Islam hates Americans because President Trump or ISIS says so? Do you “know” that Islam is peace because George W. Bush says so? Do you “know” that Islam seeks to kill blaspheming novelists because Ayatollah Khomeini says so? Do you “know” that there is no compulsion in Islam because the Quran says so? Do you “know” that Islam is a mystical religion because the Sufis say so? To ask such questions is to stand around the proverbial elephant “knowing” the whole by extrapolation from some specific part (Figure). How do we know what we “know” about Islam?

The reason this question is so important is that it arrests the cycle of ignorance, fear, and prejudice that often lead non-Muslims to struggle with the often-asked but very unhelpful question of whether Islam is a religion of peace or a religion of violence. It is neither. It is not so monolithic as to fit neatly into either box (no religion is). Rather, we need a better question. Albert Einstein is (mis)credited with stating that if he had an hour to solve an important problem, he would spend most of the time determining the right question to ask. In the case of What is Islam? I would submit that the question is simply, “Which Islam?”

Asking this simple question allows the proverbial elephant to come into view, reveals one’s situatedness, and the misinterpreted aspects of the elephant – this (tusk) as a spear; this (tail) a rope, etc. – are seen for what they are, a tusk and a tail, as one’s perspective broadens. Similarly, when a people suffering from Islamophobia manage to ask, or are asked, “Which Islam?” their perspective widens, fear lessens, and religious literacy increases.

Asking this simple question allows the proverbial elephant to come into view, reveals one’s situatedness, and the misinterpreted aspects of the elephant – this (tusk) as a spear; this (tail) a rope, etc. – are seen for what they are, a tusk and a tail, as one’s perspective broadens. Similarly, when a people suffering from Islamophobia manage to ask, or are asked, “Which Islam?” their perspective widens, fear lessens, and religious literacy increases.

Several authors have written about the rampant problem of religious illiteracy. Drs. Ali Asani and Diane Moore of Harvard University have highlighted and delineated 6 manifestations of religious illiteracy: 1) Equation of religion with doctrines, rituals, and practices; 2) The essence of religion being perceived as merely the scriptures; 3) Religious traditions seeming timeless, rigid, and monolithic; 4) Religions being seen as actors having agency; 5) The use of religion as the exclusive lens to explain the actions of the religious; and 6) An entire religious community being held responsible for the actions of individual members of that community.

A religiously literate person by contrast is able to move beyond the common devotional approach of seeing religion as simply its doctrines, rituals, and practices, and to move beyond the textual approach of seeing religion as that which arises from and is directly aligned with the scriptures (most or all of which are internally inconsistent, and all of which require interpretation; indeed, to read is to interpret based on your situatedness, since no text, one could argue, speaks for itself – not poetry, prose, or nonfiction – but rather, all require interpretation). By contrast, a contextual, or cultural-studies, approach sees religions in the various human cultural contexts in which they are situated. As such, religions are heterogeneous and malleable over time, place and person, depending on their interpretation. As opposed to the devotional and textual approaches, the cultural-studies approach is primarily concerned with the actual humans who actually practice and interpret their religion. A religiously literate person recognizes that cultural constructs such as religions are not actors with agency, i.e., they are not individuals with wills, intentions, choices and freedoms to act in the world. Failure to recognize this may lead to viewing religion as the sole cause of an individual’s actions, and by extension, à la Trump, to holding an entire religious community responsible for the actions of individual members of that community.

This religious-literacy perspective can then facilitate a better approach to the real problems associated with religion in complex ways – terrorism, etc., – that have led the innocently illiterate to become Islamophobic.